Libya Unable to Break Free from the Tethers of Millenia of Authoritarianism

May 2025 saw significant clashes in the Libyan capital of Tripoli between militias at odds with the internationally recognised Government of National Unity (GNU).

The immediate cause was the assassination of Abdelghani “Ghneiwa” al-Kikli, commander of the Tripoli-based armed group Stability Support Apparatus (SSA). The group was a major player in Tripoli, controlling the Abu Salim district and exerting considerable influence.

The assassination sparked intense fighting between the SSA and other powerful armed factions, notably the 444 Combat Brigade and al-Radaa, both nominally aligned with the GNU.

The violence, marked by heavy weaponry in civilian areas, resulted in civilian deaths, injuries, widespread property damage, and significant disruption to daily life. These clashes underscore Libya's deeply entrenched political divisions, the struggle for control over resources among armed groups, and the fragility of peace in the absence of a unified and effective state authority.

So chaotic is the situation that I routinely receive requests from a former colleague still living in Tripoli for me to tell her what is going on in her own city. With intermittent internet and no reliable news sources, she often has little idea.

While a ceasefire was eventually declared, the underlying issues and civilian protests against the government suggest continued instability and the ongoing need for accountability for violence.

Libya, of course, has been divided and in disarray ever since a 2011 NATO-backed coup deposed long-time dictator Moammar Qaddafi. The Tripoli area is largely controlled by the GNU, while the East, particularly around Benghazi, is dominated by military strongman Khalifa Haftar. Large areas of the south are controlled by tribes and militias that remain unaligned or with the terrorist group, ISIS.

The sad part of Libya’s state of affairs is that none of these alternatives are democratic. Since this configuration has been entrenched since 2011, it is unlikely to change soon. In fact, the most non-authoritarian Libya has been in the last millennia was probably when it was held by the Barbary pirates in the late 18th century.

How did Libya get here?

Ancient Period: Greek and Roman Rule (up to ~7th century CE)

Eastern Libya (Cyrenaica) was colonized by the Greeks in the 7th century BCE. The city of Cyrene became a major cultural and intellectual center.

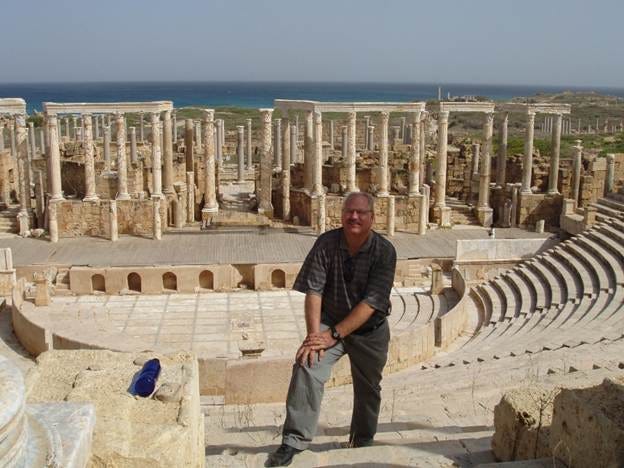

Western Libya (Tripolitania) was colonized by the Phoenicians (especially Carthage) and later taken by Rome. Under the Roman Empire, Libya prospered as a province with major cities like Leptis Magna, Sabratha, and Cyrene.

After Rome, the area became part of the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine, Empire.

As great as each of these Empires were, none could remotely be called free or democratic.

Islamic Conquest and Arab Rule (7th–16th centuries)

In the 7th century CE, Arab Muslim armies conquered the region, spreading Islam and the Arabic language. The region became part of successive Islamic empires: Umayyads, Abbasids, Fatimids, Ayyubids, and Mamluks.

Indigenous Berber dynasties also ruled at times, especially in the interior. Libya was part of trans-Saharan trade routes, connecting sub-Saharan Africa to the Mediterranean. Cities like Ghadames and Murzuq became key desert trade centers.

Autocratic, one and all.

Ottoman Rule (1551–1911)

The Ottoman Turks conquered Tripoli in 1551, making Libya part of the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans ruled indirectly, with local autonomy granted to tribal leaders and powerful families.

The Karamanli Dynasty, a semi-independent dynasty based in Tripoli, ruled with Ottoman approval from 1711-1835. They operated as quasi-pirates (Barbary corsairs), raiding legitimate Mediterranean shipping. U.S. and European powers clashed with them during the Barbary Wars (late 18th - early 19th century).

The official hymn of the US Marine Corps:

“From the Halls of Montezuma, to the shores of Tripoli”

refers to the First Barbary War in Libya.

The Ottomans reasserted direct control again after 1835, appointing governors from Istanbul.

They had limited reach in the interior, which remained under tribal or religious authority.

Libya as a Colony of Italy (1911–1943)

In 1911, Italy invaded and seized control of the country during the Italo-Turkish War. Full control took time. Italy faced strong resistance, especially from the revered resistance fighter Omar Mukhtar and the Senussi movement in Cyrenaica.

By the 1930s, Mussolini’s fascist regime had fully pacified Libya, often using brutal methods, including concentration camps and mass executions. Libya was formally declared part of Metropolitan Italy in 1939.

During World War II, Libya became a battleground. By 1943, the Allies defeated Axis forces, and Libya came under British and French military administration.

Libya under a Local Monarchy (1951–1969)

In 1951, Libya became the United Kingdom of Libya, the first African country to gain independence peacefully through the UN. King Idris I, leader of the Senussi religious order, became king. Power was divided between Tripolitania (western Libya), Cyrenaica (eastern Libya), and Fezzan (southwest Libya).

Idris ruled conservatively, with strong ties to the West (UK, US) and pro-Western Arab states. In the 1950s–60s, oil was discovered, transforming Libya’s economy. However, wealth distribution was uneven, and political freedoms were limited. Discontent with corruption, inequality, and Idris’s absence (he often stayed abroad) grew.

On September 1, 1969, Muammar Qaddafi led a bloodless military coup, overthrowing Idris and ending the monarchy.

Authoritarianism Under Qaddafi (1969–2011)

Libya under Muammar Qaddafi's rule was characterized by a highly centralized and repressive authoritarian system.

It was a classic example of an authoritarian regime. He developed a pervasive cult of personality, with his image and ideology promoted everywhere.

Qaddafi, holding no formal government post, maintained absolute power, using propaganda and state media to reinforce his image as "Brotherly Leader and Guider of the Revolution," but maintaining absolute control over all aspects of the country. State media and institutions glorified him personally, echoing totalitarian models like North Korea.

Qaddafi’s Libya had no formal constitution or political pluralism. His rule was built on a unique blend of Arab nationalism, socialism, and his own "Third Universal Theory" outlined in The Green Book, a quasi-religious political text outlining his vision of “Jamahiriya” (state of the masses). Since the ideology of the Green Book was vague and entirely dependent on Qaddafi’s own whimsical interpretations, it gave him effective unchecked authority.

Qaddafi banned political parties and replaced parliament with non-partisan "People's Committees" supposedly reflecting direct democracy, but controlled from above by him. While he nominally established a system of "direct democracy" through Basic People's Congresses and the General People's Congress (the "Jamahiriya" or "state of the masses"), in practice, these bodies were tightly controlled by Qaddafi and his "revolutionary committees."

These so-called “Revolutionary Committees” conducted ideological surveillance, arbitrary arrests, and trials under “revolutionary law,” leading to widespread abuse and suppression of civil liberties. This period was known as the “Green Terror”.

Qaddafi’s rule was marked by strict suppression of all public dissent, featuring arbitrary arrests, torture, executions, extraterritorial assassinations of exiled dissidents, and internal surveillance and repression by the Revolutionary Committees.

A pervasive police state and security apparatus, including the "revolutionary committees," monitored the population. Dissent was illegal, and a vast informant network (10–20% of the population) monitored society, comparable to the surveillance states of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq or North Korea.

Freedom of speech, assembly, and association were completely suppressed. Dissidents were imprisoned, tortured, or murdered abroad. State media was the sole source of information.

Journalists, activists, and political opponents faced threats, arbitrary detention, and violence from both state and non-state actors. Freedom of expression was severely limited, with media outlets subject to harassment and closure. Televised executions were used to instill fear and deter dissent. Political opponents and dissidents, including those abroad, were assassinated or executed, sometimes publicly.

The military was kept weak and divided to prevent coups. In its place, were so-called “people’s militia,” encouraging widespread weapons distribution under for those loyal to the regime. Elite loyalist units (Revolutionary Guard, Khamis Brigade, and his personal Amazonian Guard of elite, all-women bodyguards) protected the regime. Prisons operated with little oversight; many inmates were held without due process.

The oil industry was nationalized, and oil revenues were tightly controlled by Qaddafi and a narrow elite, reinforcing his patronage system and limiting collective action against the regime

While the regime provided free education, healthcare, and subsidized housing, wages were low, and economic opportunities outside government were limited. This created a patronage system where the state provided basic needs in exchange for political quiescence. Social engineering was attempted through education reforms, forced women’s military training, and the banning of “unsound” books.

State-owned media dominated public discourse; censorship was pervasive. The education system indoctrinated students with Qaddafi's ideology.

There simply was no power base left from which to challenge Qaddafi.

More than one of the engineers I knew from the state oil company simply chose not to go to work, spending their days moonlighting, driving gypsy taxis in the big cities, because they could make more money doing so. The going rate for a ride in the city at the time? Roughly 3 USD. They kept their official state positions only as a fiction to keep access to pensions and medical benefits.

Qaddafi also used state oil wealth to fund foreign terrorist and revolutionary groups and adventures, including the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), Spain’s ETA, Italy’s Red Brigades, the New People’s Army of the Philippines, America’s Black Panthers and Nation of Islam, and the Abu Nidal group, which carried out successful terrorist operations, including twin attacks in 1985 against airports in Rome and Vienna. He provided both financial support and sanctuary for the arch-terrorist Carlos the Jackal in the 1970s and 80s.

Gaddafi played a key role in promoting the use of oil embargoes as a political weapon for challenging the West. He supported the unsuccessful attempts for an Argentinian nuclear weapons program, in the hope of acquiring advanced military technology for Libya.

In 2003, in an attempt to reconcile with the West, Qaddafi agreed to give up all his weapons of mass destruction, including his nuclear program. Unfortunately for him, just like Saddam Hussein in Iraq, he soon lost not only his country but his life. The lesson for dictatorships like those in North Korea and Iran has been to never give up their own or suffer the same fate.

Qaddafi sent Libyan troops to aid Idi Amin in the Uganda–Tanzania War in 1978 when Amin tried to annex the northern Tanzanian province of Kagera, and Tanzania counterattacked. Gaddafi also supported Charles Taylor, the Liberian warlord-president, and Foday Sankoh, the founder of the Revolutionary United Front, both of whom were involved in the Sierra Leone Civil War.

He also sponsored the horrendous bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, causing 270 deaths, and a nightclub attack on US military members in Germany, killing three and injuring over 200 others.

“The feeling that Libya was very small and inconsequential in the Arab context made terrorism an attractive strategy to raise Libya’s platform. Terrorism was also a cheap alternative that would enable [Qaddafi] to emerge as a … leader in the Arab world.” — Diederick Vanderwalle, Political Scientist, Dartmouth University

There was little to no accountability or transparency in state finances. Private enterprise was banned; the state controlled all imports, exports, and distribution, leading to shortages and a thriving black market.

I vividly recall driving past state-owned enterprises, where every one of the hundreds of cars in the parking lots we exactly the same make, year, model and colour.

Land and wealth redistribution policies were enforced arbitrarily, often through expropriation. The country’s tribes were played against one another, the regions awarded or punished based on loyalty to Qaddafi.

All government institutions were gutted, Ministries appointed by and entirely subject to Qaddafi’s personal whims.

A Few of Just Many Examples of Qaddafi’s Government of Personal Whimsy

Leaving Libya for a weeks-long absence, my country’s foreign ministry warned me to make sure my visa paperwork was all up-to-date for my return since they’d been warned by the Libyan authorities that there would be upcoming changes. In my four weeks away, I had to submit my passport no less than three more times for changes to the Libyan Embassy overseas in order to be following proper regulations to get back.

While I was living there, a British Airways plane carrying some 300 passengers left London with all passengers being pre-cleared by Libyan Customs as the plane was leaving. In the few hours it took to fly to Tripoli, Libya suddenly changed the visa regulations. When the plane landed, it was turned around and every passenger sent back. The reason? In that short interim, one of Qaddafi’s sons had been charged in London with torturing and beating his Ethiopian maid. The visa changes were purely arbitrary to show Qaddafi’s displeasure at this insult to his family honour.

Mediterranean cruise ships were finally being granted berthing rights while I lived in Libya, providing a vitally-needed influx of tourist cash. The experiment lasted just a handful of ships before being cancelled. Either Qaddafi didn’t want outsiders seeing what was going on in Libya, or he wanted to prevent Libyans from learning what the West was really like.

Qaddafi’s whims sometimes got justice right. Our Libyan office manager took it into to his head to steal an entire room of training computers one day. Rather than getting away with it, he spent a number of years in prison for the theft.

Qaddafi’s prisons were not for the faint of heart. The Training Manager of the state oil company where I worked ended up in one of them after he accidentally killed another driver in a car accident. Like many Muslim nations, Libya observed the custom of “blood money” for deaths. The manager was put in prison for his own safety while the families negotiated a settlement. His recollection of his time there still sends shivers down my spine, although he says he was safer in prison than out on the streets while a settlement was being negotiated.

The Coup Against Qaddafi

During the wave of uprisings known as the Arab Spring, Qaddafi fell from power in 2011 after 42 years of authoritarian rule, . Protests erupted in February, initially demanding political reform, but quickly escalating into an armed revolt after government forces responded with deadly force.

The conflict became a civil war, with rebel groups gaining ground, particularly in the east. NATO intervened militarily in March, enforcing a UN-mandated no-fly zone and conducting airstrikes against Qaddafi's forces. By October, rebel fighters captured and killed Qaddafi near his hometown of Sirte, marking the end of his regime. Libya was left fragmented, unstable, and without a strong central government.

While Qaddafi’s ousting in 2011 marked the end of his dictatorship, Libya has not transitioned into a stable democracy; instead, it has experienced fragmented rule, civil war, and ongoing authoritarian practices by various actors.

Authoritarian Characteristics in Libya Today (Post-2011)

Since Qaddafi’s overthrow, Libya has plunged into instability, with the absence of a strong central authority leading to a different, but still profoundly authoritarian, landscape dominated by warring factions and militias. It is a fragmented, decentralized, and often brutal form of authoritarianism rooted in a power vacuum and the rise of powerful non-state actors.

While the exact mechanisms of authoritarianism have changed, several features persist in both the east and west.

There have been no national elections since 2014. The country's political system is dominated by military strength and foreign interference, not democratic competition. No political entity operates with a current electoral mandate, and state institutions remain divided. The competing governments (Tripoli-based GNU and eastern-based authorities under Khalifa Haftar) rule without electoral legitimacy.

No single entity has full control over the national territory, leading to a de facto state of lawlessness. Ordinary citizens have virtually no role in political affairs, which are dominated by armed factions, foreign governments (Russia, Turkey, the Gulf States, others), and criminal networks.

The rival administrations and numerous militias exert de facto control over territory. Militias function as parallel states, exerting control through violence and extortion. In both west and east, civilian institutions are subordinate to armed groups or local warlords. They often act with impunity, using violence and intimidation to maintain local power.

Powerful armed militias wield significant power and influence, often operating with total impunity. They control vast swathes of territory and resources. Security forces aligned with the rival governments operate with little accountability for human rights abuses. These groups engage in arbitrary arrests, detentions, torture, sexual violence, forced labor, and extrajudicial killings. "Confessions" extracted under torture are common.

Control over oil revenues and state resources remain a tool for political patronage and buying loyalty, echoing Qaddafi-era practices. Corruption and lack of transparency pervade government institutions.

Judicial independence is weak. The judicial system lacks independence, and arbitrary arrests, detentions, and extrajudicial killings are common. Courts are influenced by political or militia interests. Arbitrary detention, torture, and extrajudicial killings continue, often outside any legal framework.

The criminal justice system is deeply flawed, with serious due process concerns. Lawyers face harassment, military courts try civilians, and the death penalty remains in the penal code for acts of speech and association.

Elections are rare and often disputed or delayed; meaningful political participation is limited. Civil society organizations operate under threat or are co-opted by powerful groups. Dissent is crushed; journalists and activists face threats, detention, or assassination.

The media is heavily censored, partisan, and often owned or influenced by militias. Independent journalism is extremely dangerous. Various intelligence and security agencies monitor citizens, particularly in eastern Libya under Haftar. Political opponents, civil society activists, and returnees from exile face repression.

The human rights situation is widely reported to be worse than under Qaddafi in many respects, particularly concerning widespread arbitrary detention, torture, and the targeting of vulnerable populations like migrants and refugees.

Discrimination against women, ethnic minorities, and LGBTI individuals persists, with attempts by some authorities to impose stricter social norms, including compulsory veiling and restrictions on women's travel. Large groups of Africans attempting escape across the Mediterranean are routinely raped, sunk and exploited.

Lessons Learned?

If history has taught us anything, it is that democracy being successfully grafted onto deeply authoritarian cultures has had little success, outside of some notable exceptions like post-WWII Japan and South Korea.

Democracies only take root in societies where they already have the sprouts of such traditions; they need to be protected, nurtured, yearned for, and cultured over long periods of time to blossom and flourish.

The West’s democracies took centuries to develop. Why should we expect nations such as Libya or Russia to manage it overnight? Given that Libya has never had democratic, it isn’t surprising to see what is happening there now.

In essence, while Libya’s form of authoritarianism has changed from a highly centralized personalistic dictatorship to a fragmented "failed state" with multiple armed actors vying for control, the effects on the population in terms of political freedom, human rights, and the rule of law remain profoundly authoritarian and, in many cases, have deteriorated.

Not unlike after outside foreign intervention in states like Iraq and Afghanistan.